1.

Like a hungry squirrel searching for the last nut, I’m racing around the internet for medical clarity. Again.

But first: I’m fine.

2.

I’m hunting for answers. There are too many words and nothing I can touch. There is a distance in the language. Like a hug that touches only upper arms. A smile that does not reach the eyes.

After excessive searching, the words blur into meaninglessness:

you may feel . . . symptoms include . . . final stage . . . end stage.

Nobody says death. Dying is happening but also very much not happening.

3.

Ten years ago a friend and I explored death through poems and paintings.

Death is not a crisis, we agreed, then laughed and cried and shared a period of intense creativity through grief.

I like to think that period prepared me for the many people who died in the decade that followed — parents, family, and many close friends — but I don't know that it ever gets easier, or, really, that it should.

4.

I’ve lost language, the ability to write my own feelings, to say what is. I am trying to feel and not feel.

Remaking can give me words, rearrange reality.

5.

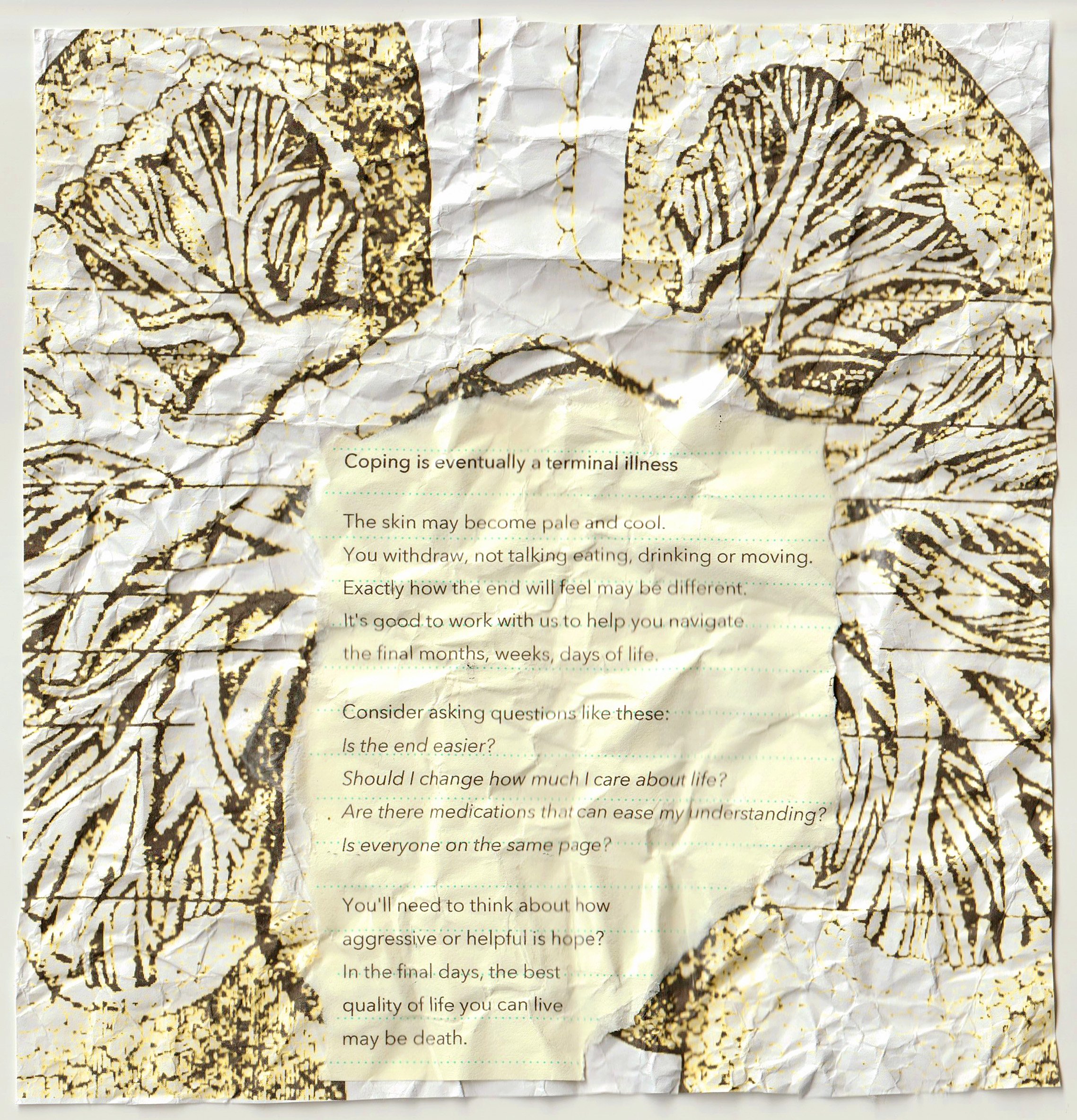

Cut, paste, create.

I call it a scramble. Some call it a cut-up or collage.

The form emerged from the Dadaists, an avant-garde art movement of the 1920s. There are many variations but the foundation of a cut-up is created by taking a finished text and cutting it in pieces with a few or single words on each piece. The pieces are then rearranged into a new text.

Over 100 years later, the cut-up technique has been used by scores of writers, musicians, and artists, from T.S. Eliot to David Bowie. Learn more here.

6.

Poet Rosmarie Waldrop refers to collage as “the splice of life,” as recounted in this excellent piece by artist Heidi Reszies that appeared in The Volta:

“I turned to collage early, to get away from writing poems about my overwhelming mother. I felt I needed to do something ‘objective’ that would get me out of myself. I took books off the shelf, selected maybe one word from every page or a phrase every tenth page, and tried to work these into structures. Some worked, some didn’t. But when I looked at them a while later: they were still about my mother.”

The poem will resemble you, said early Dadaist Tristan Tzara. What the mind has assembled—subconsciously and at any given time—will surface in your poems.

7.

There’s a freedom in the process. A joyful spark of distance and recognition. The words are not mine and yet, I remake them mine.

8.

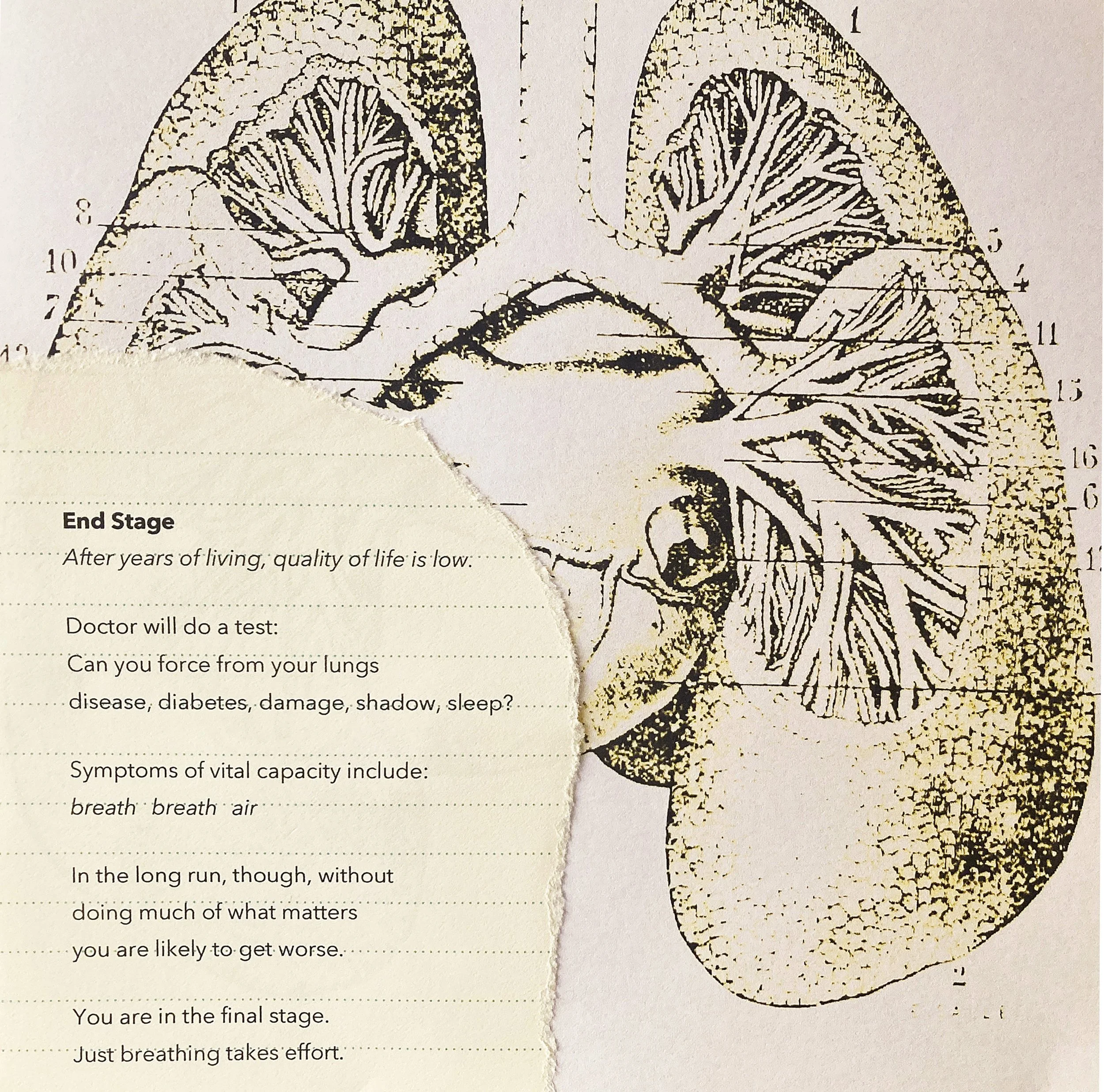

For these poems, I printed pages of medical text from webmd.com and copd.net, then cut the pages into lines of text, scrambled the order, rearranged into ‘sense.’ In this series I worked to keep key phrases intact. I did not add additional words.

I’m in each line while also standing outside each line.

The image is from Wikimedia Commons, the free media repository. The 1882 drawing, depicting bronchi and lungs of a male, appeared in Popular Science Monthly.

9.

Do these technical details matter?

Does poetry matter?

Is this exercise or art?

I have no satisfying answer. But I have the pull to create order from everything that swirls and screams, that wonders and whispers, that calls me gently to make sense, to make something.

“The mind is assembling stuff all the time,” writes poet Ralph Angel.“Poems, stories, paintings—art objects are like mirrors. No matter what we think we’re up to when we make them, they reflect precisely who we are at the time.”

_____

If you like this blog, please subscribe here for delivery directly to your email. Or can follow this blog at Feedly.

As always, thanks for reading & writing.